TOUCHY FEELY

research, pliables, and thoughts on DESIGNERS as BODIES

In this culture of profiles and digital masks, human identity has become less dependent on the physical body as a necessary means of expression. Theories on dissociation in psychology examine the separation of our minds from their surroundings as a human capacity, much like the essentially-human capacities for memory and language. With recent developments in neural imaging, neuroscientists have been able to study the complex underlying structures that support these capacities, discovering that Meaning, which develops through the combined processes such as human language, thought and memory is embodied. That is, meaning takes place in both the physical body and our famously wrinkled brain organ. The need to create an online social media identity has altered the way in which we perceive our physical self, affecting our capacity for Meaning. If we, as designers, are to be true conveyors of meaning, we must consider both the body and the mind in our design practice.

I began this process with two lines of inquiry:

- What might cause a moment of dissociation? and,

- What is the importance of the mind-body connection, as it relates to visual communication?

For an entire generation of humans born between 1981 and 1996, online profile creation came into vogue right as they (the dreaded Millennials) reached teenagehood- a crucial period of identity formation and social presentation. The magnitude of social networks available, with varying levels of formality and social specificity, has allowed this generation to selectively employ techniques shared by those undergoing psychological dissociative experiences. By using social networks to isolate and perform different aspects of the self, users compartmentalize their identities in order to choose “whichever self-state is most adaptive at a given moment,'' making use of dissociative behavior. 1

Dissociation

As written in the DSM-IV, dissociation is a “disruption in the normally integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment.” For example, a disconnect between memory and perception of the environment could produce a dissociative experience of feeling that a familiar place is suddenly completely unfamiliar. Or, perhaps a more common experience: a driver follows all traffic rules and arrives home safely without remembering any part of her journey.

2.01: “The Conceptual Unity of Dissociation: A Philosophical Argument”

Stephen E. Braude, PhD

Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond.

2009.

An amorphous definition The DSM-IV entry quoted above published in 1994 follows the initial description coined in the late nineteenth century by Pierre Janet, who viewed dissociation (which he called désagrégation) as “a kind of weakness, a failure...to integrate parts of consciousness and maintain conscious unity.” Only a few years later, researchers (e.g., Binet, 1896; Myers, 1903; Sidis, 1902) reframed dissociation as a “capacity,” much like courage or sensuality, that allows humans to divorce themselves from their own varying mental states. Even now, a century later, clinicians are still struggling to pin down a substantive description of dissociation. With his 2010 update to an earlier article published in 1995, Braude examines the assumptions beneath many of the currently competing definitions and offers a conditional analysis of dissociation.

Opposing frameworks

There are two opposing schools of thought regarding the vast range of what has been described as dissociative experiences. First, inclusivity: that dissociation manifests in varied, person-specific forms and that it can affect many different mental states.This is consistent with the idea that the ability to dissociate is another one of the human species’ emotional capacities, and though dissociative experiences encompass a range of severity, reversibility, etc., these experiences are all part of one single phenomenon. Second, and more recently, exclusivity: that nonpathological dissociation (such as daydreaming, zoning out, etc.) is taxonomically distinct from pathological dissociation (i.e. disorders that interfere with individual, social, and/or occupational functioning). That the two phenomena both use the word “dissociation” seems to be immaterial to researchers who believe them to be completely separate and uninteresting to treat as a whole. Although, seeming to reach across the aisle for a moment, Waller et al. acknowledge that nonpathological and pathological dissociation are indeed “related” (p. 34).

While the discussion of what “counts” as dissociation or not seems to have no end, as both camps argue their separate points using the same vocabulary, but with distinct semantic systems, to build up incorrect descriptions of their opponent’s position, Braude argues that the difference between the two generally agreed upon categories and all the “richness and variety” of dissociative phenomena is precisely what should be of interest to clinicians and theorists alike.

2.02: “An Update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale”

Eve Bernstein Carlson, PhD and Frank W. Putnam, MD

DISSOCIATION, 6(1).

1993.

Bernstein & Putnam originally published the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) in 1986 as a means to quantify the frequency of dissociative experiences as an aid to both researchers and mental health professionals. It is important to note, as Braude states, that the results will always be limited to what the questionnaire represents as dissociative experience.

- Some people have the experience of driving or riding in a car or bus or subway and suddenly realizing that they don’t remember what has happened during all or part of the trip. Circle a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.

0 % 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100% - Some people have the experience of being accused of lying when they do not think they have lied. Circle a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.

0 % 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100% - Some people have the experience of feeling that their body does not seem to belong to them. Circle a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.

0 % 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100% - Some people find that they sometimes are able to ignore pain. Circle a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.

0 % 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100% - Some people feel as if they are looking at the world through a fog so that people and objects appear far away or unclear. Circle a number to show what percentage of the time this happens to you.

0 % 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100%

Use of the scale In order to determine whether or not further evaluation is needed, a clinician may recommend the usage of the DES as a self-reporting tool that indicates the frequency of common dissociative experiences. The DES is not a diagnostic tool-- it merely presents scenarios of both nonpathological dissociation and pathological dissociation in varying levels of severity and asks the user to rate how often they experience them on a scale from 0% to 100%, with 0% as “I never experience this” and 100% as “I always experience this.” The original DES asked respondents to make a mark along a 100mm line, which was then scored by measuring and recording the distance of each mark from the start of the line, rounded to the nearest 5mm increment. Bernstein & Putnam replaced the 100mm lines in the update by asking respondents to simply circle the percentage that represents the frequency of their experience, again in 5% increments.

Use of the DES in translation, other cultures The DES has been translated into a number of languages, including but not limited to French, Hindi, Cambodian, Japanese, and Swedish, and has been made available in cultures across the globe. It seems that an attempt has been made to account for differing colloquialisms as well as add or delete experiences that do or do not occur in other cultures. However, the authors seem to be unsure of the validity of these translated versions, as the original was a culturally-specific pathological analysis of a phenomenon that is also still very much in question.

For those who study language in its neurological context, meaning encompasses a speaker’s holistic conceptualization of their experience. Psychologically, meaning is a combination of external and internal associations. Physically, meaning is an assembly of activated neurons, lit up in patterns created by repeated exposure to stimuli. (What those neurons and electrical signals really have to do with an individual’s understanding of their own existence and that of the world around them could be debated for however much time we have left until the nuclear apocalypse.)

Embodiment + Meaning

3.01: Neurological Meaning via Friedmann Pulvermüller

Neurons associated with physical “machinery actions” (e.g. wrist movement, shoulder rotation, etc.) are represented in what is commonly referred to as the motor cortex (see diagram 1 - left postcentral gyrus). Pulvermüller’s correlation hypothesis stated that if a spoken word has occurred repeatedly in association with a “machinery” body part, the word’s neural representation would involve both language and motor neuron activation. In a combination behavior and EEG study, German speakers were presented with verb words and pseudowords (words that appear at first glance to be real words, but that are actually meaningless) related to arm, face, and leg actions. They then had to decide as quickly as possible whether or not what they were presented with was a word or not. The study found that leg-related words were processed between 16 and 32 milliseconds slower than face-related words. Because leg neurons are further than facial neurons from perisylvian language areas (see diagram 2), this latency supports the hypothesis that a co-activation was in progress and did occur at the time of lexical decision-making.

Basically: this is neurological evidence indicating that when language is spoken, read, or received otherwise, the language areas of the brain are not activated alone. Language neurons are activated in conjunction with sensorimotor cortices according to physical, bodily associations with the lexical unit stimulus/i. (Even in the case of abstract words like “pride,” “courage,” etc., image schemas are activated, which still ignite a chain of machinery neurons.) This is embodiment- the notion that meaning relies equally on the speaker’s body and thoughts.

3.02: Linguistic Embodiment via George Lakoff and Mark Johnson

Before physical, neurological evidence for embodiment was recorded, Lakoff and Johnson approached embodiment as the origin of shared cultural metaphors. They argue that metaphor is a “natural phenomenon,” i.e. that the tendency to speak metaphorically arises from our physical bodies and our bodies’ interactions with other bodies.

As one example of embodied meaning (among many), Lakoff and Johnson draw on William Nagy’s spatialization up/down metaphors (1974) to discuss what they call orientational metaphors.

“HAPPY IS UP/SAD IS DOWN

I’m feeling up.

That boosted my spirits.

Thinking about her always gives me a lift.

I’m feeling down.

I’m depressed.

He’s really low these days…

...Physical basis: Drooping posture typically goes along with sadness and depression, erect posture with a positive emotional state.

…

GOOD IS UP; BAD IS DOWN

Things are looking up.

We hit a peak last year, but it’s been downhill ever since.

Things are at an all-time low.

He does high-quality work.

Physical basis for personal well-being: happiness, health, life and control- the things that principally characterize what is good for a person- are all UP.”

Here, they are drawing a cyclical entailment between happiness, UP-ness, and an erect physical posture (that would indicate happiness.) Further evidence for the validity of this assessment is the systematicity of the UP/DOWN metaphor. The UP/DOWN property doesn’t occur randomly and can be used productively to create new phrases that maintain the GOOD IS UP/BAD IS DOWN system.

Beyond our experiences with our own bodies in a spatial sense, Lakoff and Johnson discuss our experiences with objects outside the body as another basis for experiential, embodied meaning- ontological metaphors. For example, our cultural experience interacting with machines allows us to create a productive systematic comparison to our own minds.

“THE MIND IS A MACHINE

We’re still trying to grind out the solution to this equation.

My mind just isn’t operating today.

Boy, the wheels are turning now!

I’m a little rusty today.

We’ve been working on this problem all day and now we’re running out of steam.

…

The MACHINE metaphor gives us a conception of the mind as having an on-off state, a level of efficiency, a productive capacity, an internal mechanism, a source of energy, and an operating condition.”

It is interesting to note at this point that this book, The Metaphors We Live By, was written in 1980. Our ideas about what machines are and how we interact with them has changed drastically in the age of touch screens, the internet, and artificial intelligence. As an addition to Lakoff and Johnson’s original set of examples, I would offer this:

THE MIND IS AN OPERATING SYSTEM (OS)

Her brain must be glitching today.

I don’t have enough bandwidth to think about this right now.

Give me a second to process that information.

Recognizing the developments that have taken place in our body-metaphor vocabulary could be a crucial step forward in the field of design, not just in the realm of front-end interfaces and UI/UX. How do our changing relationships with each other in person and online change our ability to make meaning from visual means of communication?

TOUCHY FEELY

touchy feely allows for a full-body intake of information

touchy feely invades the space of the viewer to remind the viewer of their space

touchy feely embraces the absurdity of the physical body

touchy feely addresses materiality first, function second

touchy feely welcomes the discomfort of human interaction

touchy feely penetrates digital zone from the physical world

“I don’t want people to be an audience. I want everybody to be participants. Everybody involved!”

Takako Saito

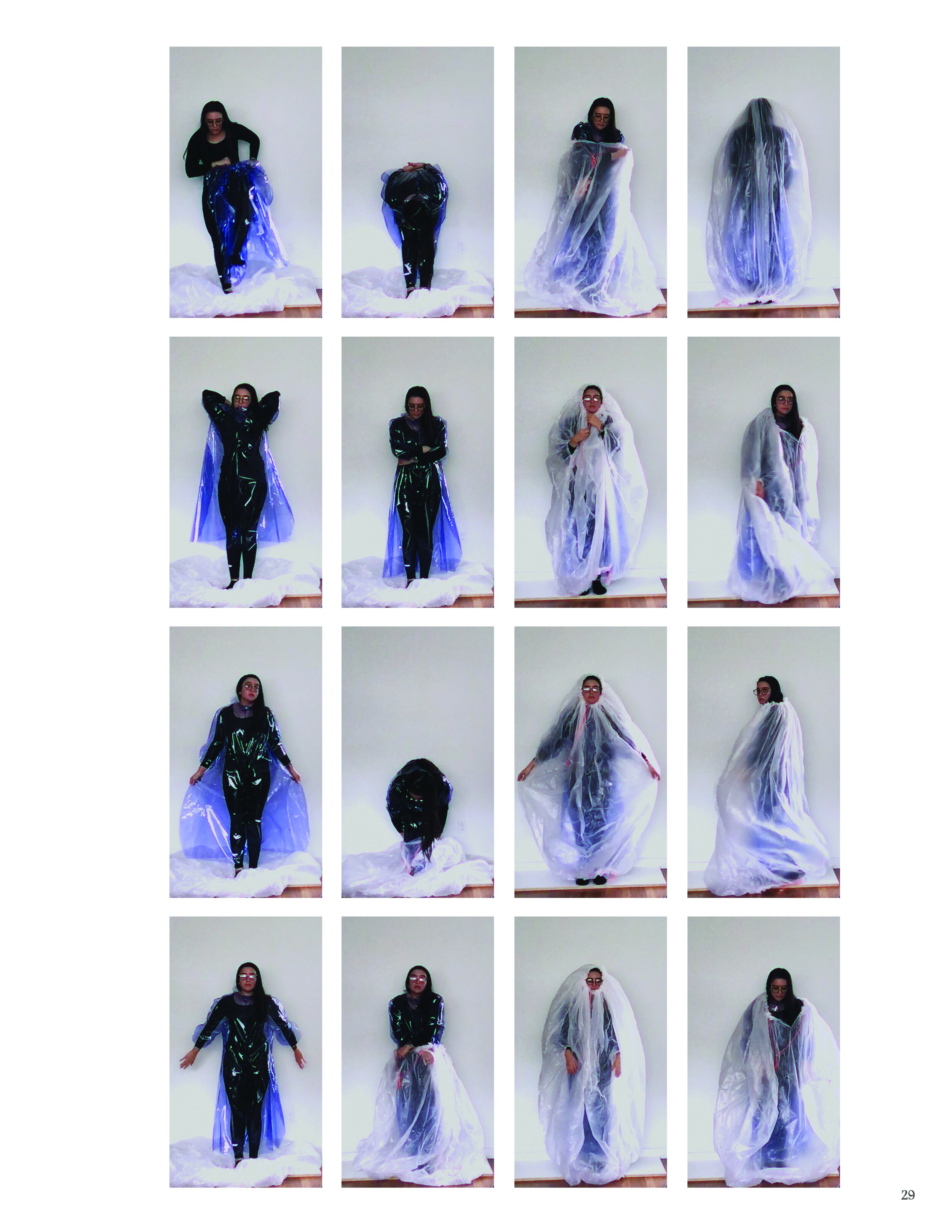

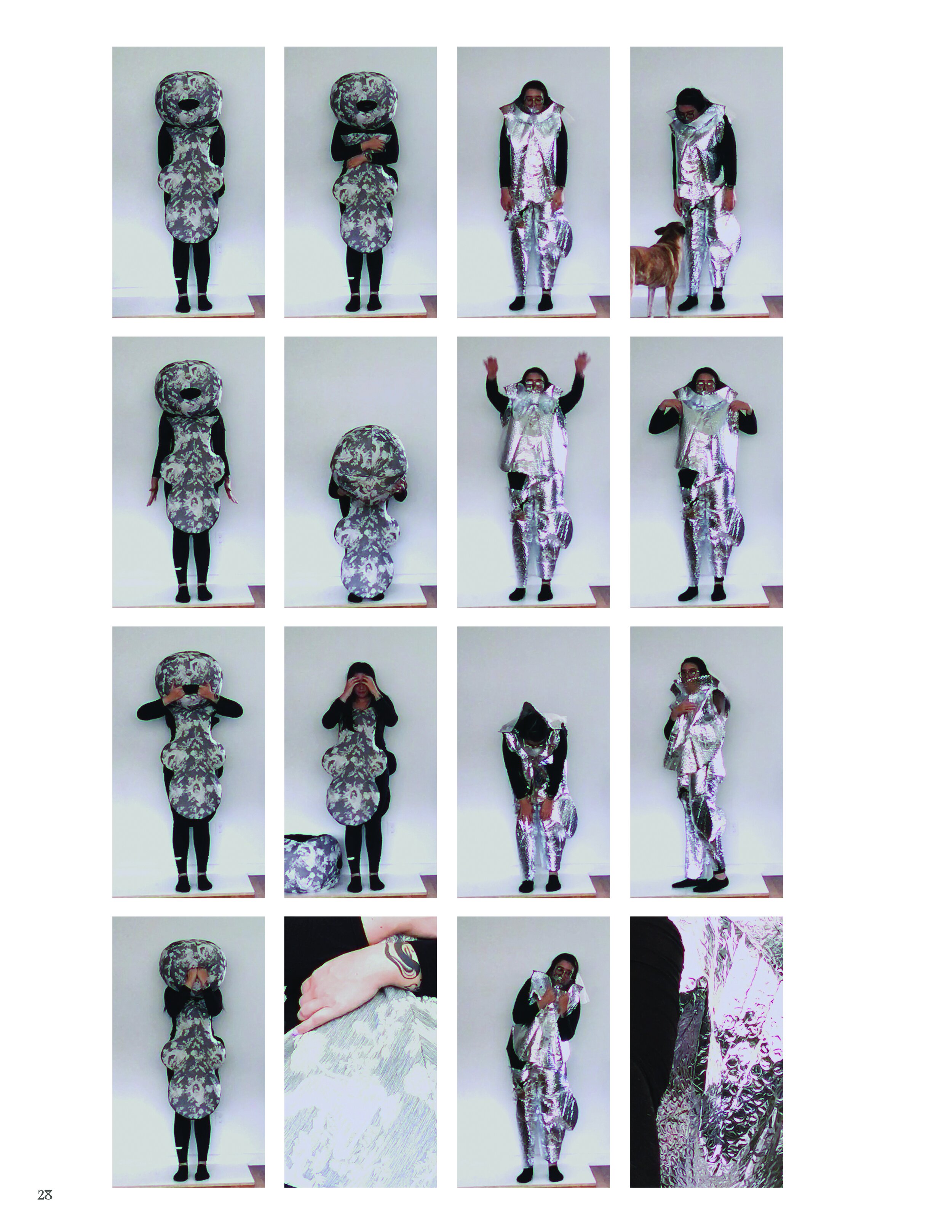

While in graduate school at the University of Houston, I spent most of my time exploring the body as a substrate with projects like Activities for Polite Aliens (with suits and a public movement workshop), Desert Game (with costumes and a large-scale outdoor game-performance), and Dead or Absent (with masks, a lecture, and a dance game-performance). I also had the privilege of being exposed to a huge variety of works that explore similar themes, both contemporary and otherwise. When planning for, and subsequently wrangling, the different media involved in this project, I looked to these three precedents for guidance and inter-dimensional support.

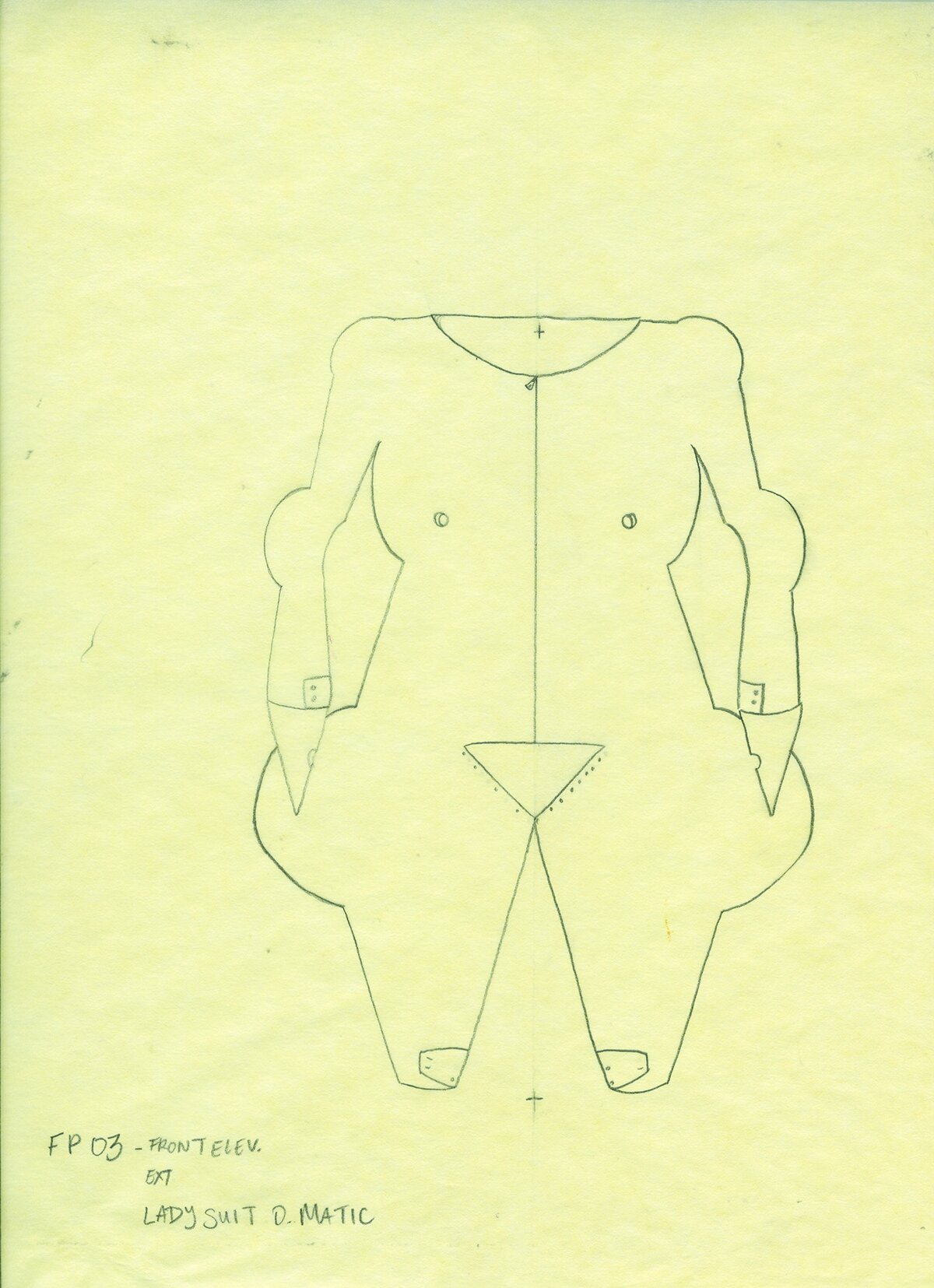

Louise Bourgeois I am interested in Louise Bourgeois’ Femme-Maison paintings as a mode of drawing that uses architecture to discuss psychological space. The paintings have a kind of isometric quality that recalls the precisely wobbly line drawings of architects Peter Eisenmann and John Hejduk. Bourgeois was not an architect, but she did think deeply about the built environment as a psycho-emotional space that shelters and traps the body and mind; in using the house-image to suffocate the women, she makes that connection explicit. Beyond the conceptual layer of house-upon-woman, formally, Bourgeois often flattens and outlines the women, presenting them in the same language as the house itself, de-personalizing the bodies until they can only be read as such.

I have leaned on this dual spatial/symbolic approach to drawing throughout the Flesh Packet process. Each suit drawing began with a desire to physically cover the space of the body while also exposing the wearer to a particular sensation. Some suits literally uncover parts of the body using cuts and voids, and others use form to disfigure or contort the wearer. For example, the Lady-O-Matic drawing contains a pinched and uncomfortable suit that both exaggerates and armors the wearer’s breasts and genitals. Like Bourgeois, I use this drawing to force a symbol onto a body-- cyborgness as a symbol of relentless evolution and efficiency, applied to a site of fatigue: the body of a woman. Unlike Bourgeois, however, I use methods of architectural sketching (via canary sketch paper, standardized detailing, and scaled measurements) rather than architectural form to process my thoughts on the juxtaposition of a built object against the organically grown human.

Takako Saito in her exhibition, You and Me, at Museum fur Gegenwartzkunst Siegen, Germany

Exchange Souvenir (detail image taken in 2019 at CAPC), Mixed media, 2001

Takako Saito at CAPC Bordeaux I stumbled upon Takako Saito’s retrospective while on an impulse trip to Bordeaux to escape the cold, grey Nantaise winter. Her bright and impeccably crafted game objects that riff on the prototypical chess board initially suggested to me that she was working in a strange fantasy land of manipulated scale and form. Some chess boards were carved wooden faces, some were painted onto rocks, and some were constructed with only one column of sixty-four black and white boxes. Yet, as I played with marbles on a wooden face mounted on astroturf against a complete stranger according to unspoken rules of our own invention, I understood that Saito’s games were completely grounded in the real world, and, to be more specific, in the spaces that exist between people. This relational approach to object-making interests me as an artist working with performance, but also as a designer who cares about making objects that humans can inhabit and use.

Outside of the chess framework, Saito has also created her own games, the rules of which she prints onto garments. The wearer activates the game by following the printed instructions and using the tools she’s sewn into the garment, such as pens, strings, or scissors. The garment’s closeness to a wearer’s body almost always plays a role in the action of the game, asking the wearer to either interact with their own body or someone else’s. In the case of the Game Shirt (pictured), the instructions read, “Pull the string out and attach to a someone.” Saito asks the wearer to first locate and detach strings from their torso, and then to possibly break some social boundaries and attach themself to “a someone.” The combined simplicity and intimacy of a gesture like this, to investigate one’s own self and another, has changed the way that I think about performance, from a set time-based work that has a planned beginning, middle and end, to an action that is sparked and set free to occur or not occur.

With the Flesh Packet project, my intent has always been to end up with a garment that could spark a moment that prompts a human to recall the limitations and possibilities of their own Packet or simply to recall that a human lives in a fleshy packet at all. The Packet suits do not contain games, per se, but they do pose an implicit challenge to the wearer. For example, Couch Packet uses a heavy, quasi-spherical helmet to both blind and weigh down the wearer. This forces the wearer to turn inward and consider their own bodily potential that has been temporarily dampened.

Screenshot from Entanglement of Movement and Meaning, filmed at Harvard Graduate School of Design

“Entanglement of Movement and Meaning: The Architect, Spatial Perception, and the Technological Body”// Oskar Schlemmer’s theater at Harvard GSD// Taught by Krzysztof Wodiczko and Ani Liu

“While architects design so much for humans, there’s often little in the curriculum that makes you think about the body---how it moves, how it feels in different configurations and in relation to space.” - Ani Liu

A friend studying at the GSD linked me to the final performance documentation from this workshop/seminar last summer after she had seen a video from my Polite Aliens movement workshop. On stage, the students were expanding on the work of the Bauhaus’ Oskar Schlemmer with slow, deliberate movement constrained and enabled by the technology of their costumes and the stage itself. Two of the vignettes show students referencing Schelmmer’s stick dance using PVC piping attached to their joints with rubber bands, but with the added layer of motion sensing and AR technology, projected over their heads. The original Stick Dance reimagines what it is to move a body in space by extending limbs and body mass past human proportions, and thus asked the performers to adjust their understanding of their own body and its boundaries. The GSD workshop’s new version takes that idea and pushes it into the 21st century built environment in which architects must account for augmented (or virtual) reality technologies and how they influence our sense of space.

Both the textual research and garment construction phases of my project exist in conversation with the premise of this workshop. While I do consciously turn my back on digital technological integration in the suits themselves, the “analog” technology of my suits is exposed and put on display in the Studio Documentation video series. The vertical videos give new, two-dimensional context to objects that were designed to primarily interact with three-dimensional space. In this way, the transference between suit and video mimics our own identities’ relationships with the digital/social-media space.

As a part of this initial foray into TOUCHY FEELY, I proposed a series of FLESH PACKETS: devices for grounding and feeling oneself, some made, some as yet un-made.

bibliography

- Philip Bromberg, Awakening the Dreamer: Clinical Journeys (Mahwah: Analytic Press, 2006).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV (Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

- Stephen Braude, “The Conceptual Unity of Dissociation: A Philosophical Argument,” Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond, edited by Paul Dell and John O’Neil (Oxfordshire: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group, 2009), 27-39.

- Eve Carlson and Frank Putnam, “An Update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale,” DISSOCIATION 6, no. 1 (March 1993): 16-27.

- Friedmann Pulvermüller and Luciano Fadiga, “Active perception: sensorimotor circuits as a cortical basis for language,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11 (2010): 351-360. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2811.

- Friedmann Pulvermüller, Bettina Mohr, and Werner Lutzenberger, “Neurophysiological correlates of word and pseudo-word processing in well-recovered aphasics and patients with right-hemispheric stroke,” Psychophysiology 41, no. 4 (May 2004). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00188.x.

- Friedmann Pulvermüller, “Brain reflections of words and their meaning,” TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 5, no. 12 (December 2001): 517-524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01803-9.

- George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live by (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), Kindle.

- Larry List, “Takako Saito: Everybody Involved!,” Takako Saito: Dreams to Do, edited by Eva Schmidt, Alice Motard, and Johannes Stahl (Koln: Snoek, 2018), 28-50.

- Deborah Wye, “Louise Bourgeois. Femme maison. 1947-1947,” Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/42/665. 2017.

- Deborah Wye, Louise Bourgeois (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982).

- Johannes Stahl, “I have dreams to do/ performances with paper cubes,” Takako Saito: Dreams to Do, edited by Eva Schmidt, Alice Motard, and Johannes Stahl (Koln: Snoek, 2018), 78-88.

- Charles Shafaieh, “In Space, Movement, and the Technological Body, Bauhaus performance finds new context in contemporary technology.” Harvard GSD News, 2019, https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2019/05/in-space-movement-and-the-technological-body-bauhaus-performance-finds-new-context-in-contemporary-technology/.

- Maggie Janik, “Entanglement of Movement and Meaning: The Architect, Spatial Perception, and the Technological Body,” filmed 2019, 15:27, https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2019/05/in-space-movement-and-the-technological-body-bauhaus-performance-finds-new-context-in-contemporary-technology/.